|

| "Gabriel José García Márquez was born on March 6, 1928 in Aracataca, a town in Northern Colombia, where he was raised by his maternal grandparents in a house filled with countless aunts and the rumors of ghosts. But in order to get a better grasp on García Márquez's life, it helps to understand something first about both the history of Colombia and the unusual background of his family."-- from the website Macondo |

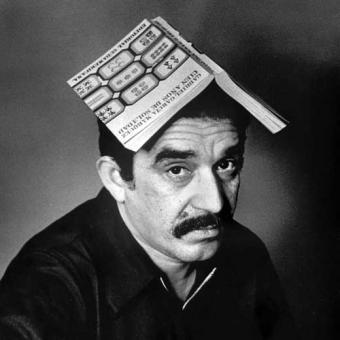

The death of the great Colombian novelist Gabriel José García Márquez was reported by The New York Times on April 17, 2014. He was 87.

For more information about García Márquez visit Macondo, an excellent website on Garcia Marquez; Macondo is also the name of the writer's fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude, a seminal novel work in Magical Realism and world literature. Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982 for his body of work. Go to his Nobel Prize page to learn more about him. Here is an interview that the Paris Review conducted with Garcia Marquez in 1981. In an excerpt from it, he talks about his literary education;

INTERVIEWER

For more information about García Márquez visit Macondo, an excellent website on Garcia Marquez; Macondo is also the name of the writer's fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude, a seminal novel work in Magical Realism and world literature. Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982 for his body of work. Go to his Nobel Prize page to learn more about him. Here is an interview that the Paris Review conducted with Garcia Marquez in 1981. In an excerpt from it, he talks about his literary education;

INTERVIEWER

How did you start writing?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

By drawing. By drawing cartoons. Before I could read or write I used to draw comics at school and at home. The funny thing is that I now realize that when I was in high school I had the reputation of being a writer, though I never in fact wrote anything. If there was a pamphlet to be written or a letter of petition, I was the one to do it because I was supposedly the writer. When I entered college I happened to have a very good literary background in general, considerably above the average of my friends. At the university in Bogotá, I started making new friends and acquaintances, who introduced me to contemporary writers. One night a friend lent me a book of short stories by Franz Kafka. I went back to the pension where I was staying and began to read The Metamorphosis. The first line almost knocked me off the bed. I was so surprised. The first line reads, “As Gregor Samsa awoke that morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect. . . .” When I read the line I thought to myself that I didn’t know anyone was allowed to write things like that. If I had known, I would have started writing a long time ago. So I immediately started writing short stories. They are totally intellectual short stories because I was writing them on the basis of my literary experience and had not yet found the link between literature and life. The stories were published in the literary supplement of the newspaper El Espectador in Bogotá and they did have a certain success at the time—probably because nobody in Colombia was writing intellectual short stories. What was being written then was mostly about life in the countryside and social life. When I wrote my first short stories I was told they had Joycean influences.

INTERVIEWER

Had you read Joyce at that time?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

I had never read Joyce, so I started reading Ulysses. I read it in the only Spanish edition available. Since then, after having read Ulysses in English as well as a very good French translation, I can see that the original Spanish translation was very bad. But I did learn something that was to be very useful to me in my future writing—the technique of the interior monologue. I later found this in Virginia Woolf, and I like the way she uses it better than Joyce. Although I later realized that the person who invented this interior monologue was the anonymous writer of the Lazarillo de Tormes.

INTERVIEWER

Can you name some of your early influences?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

The people who really helped me to get rid of my intellectual attitude towards the short story were the writers of the American Lost Generation. I realized that their literature had a relationship with life that my short stories didn’t. And then an event took place which was very important with respect to this attitude. It was the Bogotazo, on the ninth of April, 1948, when a political leader, Gaitan, was shot and the people of Bogotá went raving mad in the streets. I was in my pension ready to have lunch when I heard the news. I ran towards the place, but Gaitan had just been put into a taxi and was being taken to a hospital. On my way back to the pension, the people had already taken to the streets and they were demonstrating, looting stores and burning buildings. I joined them. That afternoon and evening, I became aware of the kind of country I was living in, and how little my short stories had to do with any of that. When I was later forced to go back to Barranquilla on the Caribbean, where I had spent my childhood, I realized that that was the type of life I had lived, knew, and wanted to write about.

Around 1950 or ’51 another event happened that influenced my literary tendencies. My mother asked me to accompany her to Aracataca, where I was born, and to sell the house where I spent my first years. When I got there it was at first quite shocking because I was now twenty-two and hadn’t been there since the age of eight. Nothing had really changed, but I felt that I wasn’t really looking at the village, but I was experiencing it as if I were reading it. It was as if everything I saw had already been written, and all I had to do was to sit down and copy what was already there and what I was just reading. For all practical purposes everything had evolved into literature: the houses, the people, and the memories. I’m not sure whether I had already read Faulkner or not, but I know now that only a technique like Faulkner’s could have enabled me to write down what I was seeing. The atmosphere, the decadence, the heat in the village were roughly the same as what I had felt in Faulkner. It was a banana-plantation region inhabited by a lot of Americans from the fruit companies which gave it the same sort of atmosphere I had found in the writers of the Deep South. Critics have spoken of the literary influence of Faulkner, but I see it as a coincidence: I had simply found material that had to be dealt with in the same way that Faulkner had treated similar material.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ and Magical Realism For information re: magical realism, see J. Kip Wheeler's webpage of literary terms; if this link does not work I have a link to Wheeler's webpage under the On Writing section on the right side of the blog; look for Literary Terms by Dr. L. Kip Wheeler, and follow the links to magical realism. Also, I invite you to read about narrator, epiphany and motif at Wheeler's site.

Salman Rushdie's Magic in the Service of Truth: Gabriel García Márquez’s Work Was Rooted in the Real appeared in The New York Times, April 21, 2014. Rushdie argues that writers like García Márquez show how "imagination is used to enrich reality, not to escape from it." He is concerned that "[t]he trouble with the term 'magic realism,' el realismo mágico, is that when people say or hear it they are really hearing or saying only half of it, 'magic,' without paying attention to the other half, 'realism.' But if magic realism were just magic, it wouldn’t matter. It would be mere whimsy — writing in which, because anything can happen, nothing has effect. It’s because the magic in magic realism has deep roots in the real, because it grows out of the real and illuminates it in beautiful and unexpected ways, that it works."

The first 11 minutes of the

documentary Garcia Marquez: A Witch Writing

If the video is not appearing, try this link.

T.C. Boyle on GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ:

"The book that spoke to me [when Boyle was probably in his early 20s] was imagined by my enduring hero, Gabriel García Márquez, and it is One Hundred Years of Solitude. Many before me have spoken of its magisterial blend of magic, humor, and history, so I will let all that slide and address one of García Márquez's short stories that appeared around that time in the New American Review, "A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings." This is the story of a decrepit angel coming for a sick child in a storm on the Caribbean coast of Cólombia. The storm drives him down out of the sky to land in a very unangelic heap in the backyard of the child's parents, where he is confined in a chicken house, amongst the other winged and feathered creatures. The story is a sly (and yes, wicked) satire of the forms and strictures of the Catholic church, and it places the miraculous in the context of the ordinary--again, just as in real life. And oh yes, when I think of that story and that book, I can't help recalling the doggy smell of the stone gatehouse--we had three magnificent and magnificently stinking dogs at the time--and of the great leaping blazes we would build nightly in the old fireplace to keep the frost at bay." (from an Amazon.com page republished on Reinhard Dhonat's site devoted to Boyle.)

|

| The house in Aracataca, Colombia where Garcia Marquez, aka Gabo, was born in 1928. (El Espectador; with thanks to Sean Dolan)

from the Paris Review interview with García Márquez, 1981:

INTERVIEWER

Can you name some of your early influences?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

. . . . Around 1950 or ’51 another event happened that influenced my literary tendencies. My mother asked me to accompany her to Aracataca, where I was born, and to sell the house where I spent my first years. When I got there it was at first quite shocking because I was now twenty-two and hadn’t been there since the age of eight. Nothing had really changed, but I felt that I wasn’t really looking at the village, but I was experiencing it as if I were reading it. It was as if everything I saw had already been written, and all I had to do was to sit down and copy what was already there and what I was just reading. For all practical purposes everything had evolved into literature: the houses, the people, and the memories. I’m not sure whether I had already read Faulkner or not, but I know now that only a technique like Faulkner’s could have enabled me to write down what I was seeing. The atmosphere, the decadence, the heat in the village were roughly the same as what I had felt in Faulkner. It was a banana-plantation region inhabited by a lot of Americans from the fruit companies which gave it the same sort of atmosphere I had found in the writers of the Deep South. Critics have spoken of the literary influence of Faulkner, but I see it as a coincidence: I had simply found material that had to be dealt with in the same way that Faulkner had treated similar material.

From that trip to the village I came back to write Leaf Storm, my first novel. What really happened to me in that trip to Aracataca was that I realized that everything that had occurred in my childhood had a literary value that I was only now appreciating. From the moment I wrote Leaf Storm I realized I wanted to be a writer and that nobody could stop me and that the only thing left for me to do was to try to be the best writer in the world. That was in 1953, but it wasn’t until 1967 that I got my first royalties after having written five of my eight books.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that it’s common for young writers to deny the worth of their own childhoods and experiences and to intellectualize as you did initially?

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ

No, the process usually takes place the other way around, but if I had to give a young writer some advice I would say to write about something that has happened to him; it’s always easy to tell whether a writer is writing about something that has happened to him or something he has read or been told. Pablo Neruda has a line in a poem that says “God help me from inventing when I sing.” It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality. The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.

|

From that trip to the village I came back to write Leaf Storm, my first novel. What really happened to me in that trip to Aracataca was that I realized that everything that had occurred in my childhood had a literary value that I was only now appreciating.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ in The New Yorker

The New Yorker has published numerous stories by García Márquez and a profile of him. Here is the magazine's post with links.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Interview

William Kennedy's interview with García Márquez. It appeared in The Atlantic, January 1973 under the title, "The Yellow Trolley Car in Barcelona, and Other Visions."

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Obituaries

The New Yorker has published numerous stories by García Márquez and a profile of him. Here is the magazine's post with links.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Interview

William Kennedy's interview with García Márquez. It appeared in The Atlantic, January 1973 under the title, "The Yellow Trolley Car in Barcelona, and Other Visions."

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Obituaries

The New York Times, April 17, 2014 has an extensive report on his life and death. Many other news outlets around the world, including the Los Angeles Times, CNN, Time, The Guardian, and The New Yorker declare his importance.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Farewell Letter

The infamous "farewell letter" attributed to García Márquez is a fake. He didn't write it. It was reprinted many times. If you wish to read it, click on this link.

GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ Farewell Letter

The infamous "farewell letter" attributed to García Márquez is a fake. He didn't write it. It was reprinted many times. If you wish to read it, click on this link.

Diego, Chris, Bea, Ariana

ReplyDelete1. Why would they realize until now that they want to come together and form a tighter-knit community?

2. What qualities does the Marquez's writing have (especially in relation the plot) that makes it so engaging and mystical?

Altina Arakelian

ReplyDeleteSelicia Hon

Perla Guerara

Kevin Alvarez

1. Where did Esteban come from ?

2. Why did they younger people at first name him Lautaro

Charissa Cons, Cynthia Ponciano, Jesus Calvillo

ReplyDelete1. Where did the name estaban come from?

2. What kind of tribe are these and men and women from? What village? And where?

Mia Sanga, Gissela Galvan, Ricky Zheng, Rebecca Padilla

ReplyDelete1.) Why did they name the drowned man Esteban?

2.) What is "Esteban's" life history?

1. Why were the people of the village so calm with a dead man being washed up on shore?

ReplyDelete2. Where did he come from? was he a giant where he came from or only to the village people?

Jett Even, Destiny De La Torre, Julian Munoz, Justin Lee

Nery Munos

ReplyDeleteMia Yang

Michele Raad

Nicholas Anduaga

1. Why were the names Esteban and Lautaro chosen?

2. Why did the men change their point of view of Esteban after the handkerchief was removed?

June Fan

ReplyDeleteKenny Voug

Joanna Aragon

Valery Dominguez

1. What was the setting of the story?

2. Why didn't the villagers try and find the drowned man's family if he had any?

Thanks everybody for your great questions!

ReplyDelete