Do you see the photograph, above? Of course you do. It's of Junot Diaz, born December 31, 1968, and it accompanies an interview with him called "Junot Díaz: Growing the Hell Up" that ran in Rablè International. It is a good interview as he talks about his writing, reading, the Dominican Republic where he was born, New Jersey where he grew up, and how his mother motivated him. He recalls, "Mom was like, 'Either you’re taking college classes, even though you’re working full time, or you can live on the street.' And it was a smart thing for her to do. Because if I hadn’t been kept busy, I would have definitely just lost my way. I was one of those kids who, I gotta tell you, man, I was not one of the smartest kids growing up. But who is?"

Díaz is critically acclaimed, best known for his novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Published in 2007, it won the National Book Critics Circle Award and Pulitzer Prize for fiction. It has been translated for readers around the world; translator Achy Obejas describes the process from English to Spanish/Dominican. (If you do get around to reading the novel, you may want to keep the annotated Oscar Wao nearby; thanks to a mysterious Kim for her hard work and creating the website.) In 2012 Díaz was awarded a MacArthur "genius grant," a $500,000 prize. To learn about his life and career, you can take a look at his website, which also discusses his publications.

|

| An Indonesian edition of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao |

Interview with Junot Díaz

by Mary Beth Keane

by Mary Beth Keane

Mary Beth Keane: Congratulations on This Is How You Lose Her being named a Fiction Finalist for the 2012 National Book Award. I know this must be a busy time for you, so many thanks in advance for doing this. How did you learn you’d been named a Finalist and what was your first response?

Junot Díaz: I was of course in a bookstore buying books—which seems to be where I always am—in Kinokuniya to be precise—when Harold Augenbraum rang me up on my cell. I first thought he was going to hit me up again to be on a jury and then he told me the good news and I have to say I was frankly floored. I put my back against Naruto and just breathed a while.

MBK: Of the five Finalists this year, This Is How You Lose Her is the only collection of short stories. What, in your opinion, is the state of the short story today?

JD: Yup, the only short story collection amongst all these wonderful heavy-hitting novels—let's just say it leaves one feeling a little like the Red Shirts in an old Star Trek episode. But anyway, as for the short story itself I believe the form is having a golden age. Sure, some publishers and some readers are biased against it but right now the form has so many extraordinary practitioners, from Pam Houston to Edward P. Jones, from Chris Lee to Jennine Capo Crucet, from Thomas Glave to Tania James to Maureen F. McHugh—if you love to read short stories like I do you can read a perfect tale nearly every day and never be without.

Click here to read the rest of this interview.

Interview with Junot Díaz

by Bill Moyers

From the Bill Moyers television show webpage. The interview was conducted December 28, 2012.

Junot Díaz & Stephen Colbert & Others

Díaz is a man of strong character. He appeared on the Colbert Report, twice. You can watch the June 19, 2008 and the March 26, 2013 interviews by clicking on the date for each.

Díaz also did interviews with Literal Magazine: Latin American Voices, The Daily Beast, Grantland, Latin Post, and Nerdsmith. The great Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat spoke with Díaz for BOMB Magazine. Díaz gave a talk at Harvard's Nieman Foundation, a program devoted to narrative nonfiction writing. You can listen to two NPR interviews with Díaz, broadcast on September 11, 2012 and October 5, 2012. The New York Times published a profile of Diaz in its magazine, September 27, 2012; it's called "Junot Diaz Hates Writing Short Stories".

Essays by Junot Díaz

Homecoming, With Turtle

by Junot Díaz

The New Yorker, June 14, 2004

He'll Take El Alto

Dominican Food in Northern Manhattan

by Junot Díaz

Gourmet, September 2007

Apocalypse

What Disasters Reveal

by Junot Díaz

Boston Review, May 1, 2011

The four writers, Díaz, Danticat, Kurlansky, and Alvarez, also co-authored "In the Dominican Republic, Suddenly Stateless," which ran in the Los Angeles Times, November 10, 2013. They examined how "Dominicans of Haitian descent are losing their citizenship as their nation reinstates an old form of racism."

|

| A Croation edition of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao |

Interview with Junot Díaz

by Bill Moyers

From the Bill Moyers television show webpage. The interview was conducted December 28, 2012.

"Díaz joins Bill [Moyers] to discuss the evolution of the great American story. Along the way he offers funny and perceptive insights into his own work, as well as Star Wars, Moby Dick, and America’s inevitable shift to a majority minority country.

"There is an enormous gap between the way the country presents itself and imagines itself and projects itself and the reality of this country,” Díaz tells Bill. “Whether we’re talking about the Latino community in North Carolina. Whether we’re talking about a very active and I think in some ways very out queer community across the United States. Or whether we’re talking about an enormous body of young voters who are either ignored or sort of pandered to or in some ways, I think that what we’re having is a new country emerging that’s been in the making for a long time.”

"There is an enormous gap between the way the country presents itself and imagines itself and projects itself and the reality of this country,” Díaz tells Bill. “Whether we’re talking about the Latino community in North Carolina. Whether we’re talking about a very active and I think in some ways very out queer community across the United States. Or whether we’re talking about an enormous body of young voters who are either ignored or sort of pandered to or in some ways, I think that what we’re having is a new country emerging that’s been in the making for a long time.”

Watch the full Bill Moyers interview with Díaz here.

|

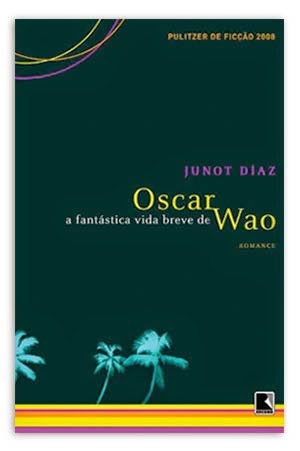

| A Brazilian edition of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao |

Díaz is a man of strong character. He appeared on the Colbert Report, twice. You can watch the June 19, 2008 and the March 26, 2013 interviews by clicking on the date for each.

"Geeking Out with Junot Diaz."

Does he like comic books? He loves comic books.

Watch the video.

Watch the video.

This is the deluxe edition of Junat Diaz's This is How You Lose Her.

Jaime Hernandez contributed the art to this edition. His bio appears here.

Its deluxe edition was named one of the best books of 2013 by The Washington Post.

More Interviews & Talks with Junot Díaz |

| Art by Jaime Hernandez for the deluxe edition of Diaz's This is How You Lose Her. More examples of Hernandez's illustrations for Diaz's collection can be found here. |

Díaz also did interviews with Literal Magazine: Latin American Voices, The Daily Beast, Grantland, Latin Post, and Nerdsmith. The great Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat spoke with Díaz for BOMB Magazine. Díaz gave a talk at Harvard's Nieman Foundation, a program devoted to narrative nonfiction writing. You can listen to two NPR interviews with Díaz, broadcast on September 11, 2012 and October 5, 2012. The New York Times published a profile of Diaz in its magazine, September 27, 2012; it's called "Junot Diaz Hates Writing Short Stories".

|

| A Netherlands edition of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao |

Junot Díaz, Octavia Butler and PCC

Here's a bit of trivia about Díaz and Pasadena City College. Octavia Butler, the late science fiction writer (June 22, 1947 – February 24, 2006) and PCC alum, A.A. 1968, is Díaz's "personal hero," something he revealed in an interview with The New York Times of August 30, 2012. When asked which three writers, living or dead, he would invite to dinner, he picked Butler "because she’s my personal hero, helped give the African Diaspora a future (albeit a future nearly as dark as our past) and because I’d love to see her again." Here is a brief interview with Butler, a video interview with Charlie Rose (Part I and Part II), and her obituary.

|

| A Turkish edition of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao |

Essays by Junot Díaz

Homecoming, With Turtle

by Junot Díaz

The New Yorker, June 14, 2004

That summer! Eleven years ago, and I still remember every bit of it. Me and the girlfriend had decided to spend our vacation in Santo Domingo, a big milestone for me, one of the biggest, really: my first time “home” in nearly twenty years. (Blame it on certain “irregularities” in paperwork, blame it on my threadbare finances, blame it on me.) The trip was to accomplish many things. It would end my exile—what Salman Rushdie has famously called one’s dreams of glorious return; it would plug me back into that island world, which I’d almost forgotten, closing a circle that had opened with my family’s immigration to New Jersey, when I was six years old; and it would improve my Spanish. As in Tom Waits’s song “Step Right Up,” this trip would be and would fix everything.

Maybe if I hadn’t had such high expectations everything would have turned out better. Who knows? What I can say is that the bad luck started early. Two weeks before the departure date, my novia found out that I’d cheated on her a couple of months earlier. Apparently, my ex-sucia had heard about our planned trip from a mutual friend and decided in a fit of vengeance, jealousy, justice, cruelty, transparency (please pick one) to give us an early bon-voyage gift: an “anonymous” letter to my novia that revealed my infidelities in excruciating detail (where do women get these memories?). I won’t describe the lío me and the novia got into over that letter, or the crusade I had to launch to keep her from dumping me and the trip altogether. In brief, I begged and promised and wheedled, and two weeks later we were touching down on the island of Hispaniola. What do I remember? Holding hands awkwardly while everybody else clapped and the fields outside La Capital burned. How did I feel? All I will say is that if you fused the instant when heartbreak occurs to the instant when one falls in love and shot that concoction straight into your brain stem you might have a sense of what it felt like for me to be back “home."

To read all of Diaz's essay on Santo Domingo click here.

Dominican Food in Northern Manhattan

by Junot Díaz

Gourmet, September 2007

In those early days of our immigration (so the story goes), we Dominicans had no restaurants. There were no Caridads, no Malecons, no chimichurri trucks anywhere in sight. The first of us survived primarily on other people’s larders. On NY street food, on Puerto Rican fritura, on Cuban black beans. The street stuff—the hot dogs, the hamburgers, the pizza—was worth bragging about on visits to the Island, but nothing you could hang a life on. As for the Cuban and Puerto Rican grub—familiar, yes, but when you’re a thousand miles from home, cut off from your cultural and ancestral ley lines—and dying for a taste of mangú—not familiar enough.

Been 40 years since those bad old days, and much has changed for us Dominicans, especially in New York. Where before we were a couple thousand souls scattered throughout the five boroughs, today we’re nearly a million strong in the greater metropolitan area, the majority concentrated in upper Manhattan (or El Alto, as it is known in Spanish). Starting at 135th Street on the west side and running all the way into Washington Heights and Inwood, Alto Manhattan is to the Dominican community what Miami is to Cubans, what the LES and El Barrio used to be to Puerto Ricans—the Ground Zero of our New Jerusalem, the place we settled most successfully in the wake of our diaspora. It’s here where we achieved the condition that must have seemed unimaginable to our first sojourners: density. Density: not great for childhood or privacy, but wonderful for community and of course for the appetite. The “forefathers” might have lived off other people’s larders, but that’s not something their children have to worry about. We actually have the opposite problem. If you’re in upper Manhattan and can’t score a decent taste of Dominican cooking, either you’re trying real hard to screw up, or something’s very wrong with your luck. The trouble is not finding good spots but simply trying to decide which ones to choose.

Been 40 years since those bad old days, and much has changed for us Dominicans, especially in New York. Where before we were a couple thousand souls scattered throughout the five boroughs, today we’re nearly a million strong in the greater metropolitan area, the majority concentrated in upper Manhattan (or El Alto, as it is known in Spanish). Starting at 135th Street on the west side and running all the way into Washington Heights and Inwood, Alto Manhattan is to the Dominican community what Miami is to Cubans, what the LES and El Barrio used to be to Puerto Ricans—the Ground Zero of our New Jerusalem, the place we settled most successfully in the wake of our diaspora. It’s here where we achieved the condition that must have seemed unimaginable to our first sojourners: density. Density: not great for childhood or privacy, but wonderful for community and of course for the appetite. The “forefathers” might have lived off other people’s larders, but that’s not something their children have to worry about. We actually have the opposite problem. If you’re in upper Manhattan and can’t score a decent taste of Dominican cooking, either you’re trying real hard to screw up, or something’s very wrong with your luck. The trouble is not finding good spots but simply trying to decide which ones to choose.

To read all of Diaz's essay on Dominican food click here.

For Dominican food recipes, see Aunt Clara's Kitchen.Apocalypse

What Disasters Reveal

by Junot Díaz

Boston Review, May 1, 2011

ONE

On January 12, 2010 an earthquake struck Haiti. The epicenter of the quake, which registered a moment magnitude of 7.0, was only fifteen miles from the capital, Port-au-Prince. By the time the initial shocks subsided, Port-au-Prince and surrounding urbanizations were in ruins. Schools, hospitals, clinics, prisons collapsed. The electrical and communication grids imploded. The Presidential Palace, the Cathedral, and the National Assembly building—historic symbols of the Haitian patrimony—were severely damaged or destroyed. The headquarters of the UN aid mission was reduced to rubble, killing peacekeepers, aid workers, and the mission chief, Hédi Annabi.

The figures vary, but an estimated 220,000 people were killed in the aftermath of the quake, with hundreds of thousands injured and at least a million—one-tenth of Haiti’s population—rendered homeless. According to the Red Cross, three million Haitians were affected. It was the single greatest catastrophe in Haiti’s modern history. It was for all intents and purposes an apocalypse.

TWO

Apocalypse comes to us from the Greek apocalypsis, meaning to uncover and unveil. Now, as James Berger reminds us in After the End, apocalypse has three meanings. First, it is the actual imagined end of the world, whether in Revelations or in Hollywood blockbusters. Second, it comprises the catastrophes, personal or historical, that are said to resemble that imagined final ending—the Chernobyl meltdown or the Holocaust or the March 11 earthquake and tsunami in Japan that killed thousands and critically damaged a nuclear power plant in Fukushima. Finally, it is a disruptive event that provokes revelation. The apocalyptic event, Berger explains, in order to be truly apocalyptic, must in its disruptive moment clarify and illuminate “the true nature of what has been brought to end.” It must be revelatory.

To read all of Díaz's essay on Haiti click here.

|

| Edwidge Danticat, author of the memoir Brother, I'm Dying, pictured at left, above, and Díaz share much in common as immigrants, writers, and political activists. Danticat was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on January 19, 1969; Díaz in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic on December 31, 1968. Danticat and Díaz both won the National Book Critics Award in 2008 for Brother, I'm Dying and The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, respectively. They co-authored "The Dominican Republic's War On Haitian Workers," an op-ed piece which ran in The New York Times, November 20, 1999, Danticat and Diaz have also appeared on programs together; they can be heard on a Lannan Foundation podcast, from November 30, 2005. |

A Letter re: the Dominican Republic and Haiti by Junot Díaz, Edwidge Danticat et al (in response to "Dominicans of Haitian Descent Cast Into Legal Limbo By Court", The New York Times, October 24, 2013; the letter can be found below and on The New York Times editorial page, published October 31, 2013.)

To the Editor:

For any who thought that there was a new Dominican Republic, a modern state leaving behind the abuse and racism of the past, the highest court in the country has taken a huge step backward with Ruling 0168-13.

According to this ruling, the Dominicans born to undocumented parents are to have their citizenship revoked. The ruling, retroactive to 1929, affects an estimated 200,000 Dominican people of Haitian descent, including many who have had no personal connection with Haiti for several generations.

Such appalling racism is a continuation of a history of constant abuse, including the infamous Dominican massacre, under the dictator Rafael Trujillo, of an estimated 20,000 Haitians in five days in October 1937.

One of the important lessons of the Holocaust is that the first step to genocide is to strip a people of their right to citizenship.

What will happen now to these 200,000 people — stateless with no other country to go to?

The ruling will make it challenging for them to study; to work in the formal sector of the economy; to get insurance; to pay into their pension fund; to get married legally; to open bank accounts; and even to leave the country that now rejects them if they cannot obtain or renew their passport. It is an instantly created underclass set up for abuse.

How should the world react? Haven’t we learned after Germany, the Balkans and South Africa that we cannot accept institutionalized racism?

Mark Kurlansky

Junot Díaz

Edwidge Danticat

Julia Alvarez

New York, Oct. 29, 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment